How can a country replace a bad regime with a good one? The only possible answer to this question is a resounding and unequivocal “that depends”.

The success of such a transition is predicated on numerous variables. If, for example, a bad regime is an aberration in the country’s generally benign history, this should be a matter of simple backtracking.

If, on the other hand, political goodness is historically scant, things become trickier. There will always be an intellectual elite capable of realising the wicked nature of the present regime – that part is omnipresent.

However, if called to action, such an elite is guaranteed to do more harm than good unless it also envisages a clear pathway to virtue, even understood only in limited political terms.

Believing, as neoconservatives do, that there exists one pathway for all is a woeful lapse of historical knowledge, political nous and indeed common sense. Political panaceas are as impossible as pharmaceutical ones.

For the Phoenix of goodness to rise out of the ashes of wickedness, the bird has to be sent in flight by an intellectually powered idea: the Word is at the beginning of good statecraft as much as of everything else.

This idea can’t be borrowed ready-made and wholesale from someone else. That works about as well as a hired dinner suit: it doesn’t. Some elements of foreign practices can be successfully imported, but their square angles need to be filed off for them to fit into the round holes of the indigenous ethos.

Without overburdening you with historical references, here’s just one: Lee Kuan Yew, who governed Singapore for 30 years and led it to the best destination the country could possibly have reached.

LKY decided that Singapore could only succeed if it adopted both the language and the traditional economic policies of the Anglo-Saxons, but without losing some essential aspects of its own tradition coded into the nation’s DNA.

This effort was a spectacular success: Singapore became prosperous, clean (if a tad antiseptic) and law-abiding. What it didn’t become is a carbon copy of British or American democracy – LKY realised that would be impossible to wedge into the country’s tradition.

Such political wisdom doesn’t exist in Russia and never has. The list of sublime Russian writers will reel off one’s tongue without a moment’s hesitation; the list of interesting metaphysical thinkers will be shorter but still impressive.

However, one struggles to find a single valuable contribution Russians have made to political or legal theory. Characteristically, Nikolai Lossky’s History of Russian Philosophy devotes 57 pages to Vladimir Soloviov (d. 1900, one of those interesting metaphysical thinkers I mentioned) and only two to all the Russian philosophers of law combined.

If Russian political thought was embryonic a century ago, it has since managed to go backwards even from that inauspicious position. Today’s Russian political commentators sound like little girls who thrust their little feet into Mummy’s shoes, thinking they could thereby become just like Mummy.

They want Russia to be like the West, but without 3,000 years of the same agonising, today meandering, tomorrow kaleidoscopic development informed by the best political, legal, religious and social thinkers the world has ever produced.

I’m specifically talking about the liberal commentators, those who sound perfectly grown-up when pointing out the evil nature of Putin’s kleptofascist regime. That part is easy for anyone with eyes to see, provided those eyes aren’t clouded by the noxious fumes of ideology or the fog of ignorance.

Many of them point out Putin’s age and set their hopes on anno domini – the good colonel is 67, so another 20 years of the same thievery, oppression and rabid aggression is unlikely.

That is, barring a popular uprising many of them see as likely. The Putin junta will be swept away and… Yes, quite. They don’t really know, and I for one shudder to think what may come next, given the quality of the opposition.

Those liberals resemble Lenin’s Bolsheviks in one respect: they want to dislodge the present regime and put themselves in power, but without much of a clue about how to use that power. When pressed, they spout general phrases suggesting that Russia could simply follow ‘the West’, with all its institutions and practices.

I put ‘the West’ in quotes because those Russians see it as an idealised monolith, a faithful reflection of the worldview spun by the liberal press: the Guardian, Le Monde and the New York Times are to them the sole prophets of ‘Western’ virtue.

Mention to them that the West has another, conservative strain of political wisdom, one that predates those venerable publications by millennia, and they’ll start flapping their wings like the aforementioned Phoenix. The word ‘conservatism’ is irreparably compromised in their minds by its association with Putin.

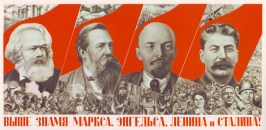

Conservatism to them means a KGB government with a KGB Church in tow, a small KGB/gangster elite looting billions from an impoverished population, suppressed freedom of speech, obedient courts passing sentences predetermined in the Kremlin, rehabilitation of Stalin, imperial effrontery, a constant stream of lies on TV, homosexuals and ethnics beaten up in the street, peaceful demonstrations only resulting in busted heads and arrests etc.

Fair enough, ‘conservatism’, when used as quasi-traditionalist camouflage for Putin’s kleptofascism does mean all those things. However, those liberals don’t seem to be aware that it has nothing to do with the conservatism that produced all those institutions they profess to admire.

Let me show you what I mean by translating a typical piece of writing. The author, one of the best the opposition has, is writing an obituary for his colleague, Yevgeniy (diminutively ‘Zhenia’) Ikhlov:

“Zhenia and I belonged to the same camp… the camp of defenders of the Enlightenment values. The values of rationalism, humanism and progress. The values of liberty and human rights.

“In our time of rampant utilitarianism, cynicism and post-modernism these values are spat upon and mocked as naïve delusions of a Western civilisation in its youth. But Zhenia believed in them. He believed in liberty… Human rights for all. The rights of man and citizen. In the very 1789 sense… Like me, Zhenia belonged to the camp of Liberty-Equality-Fraternity…”

Concentration camps ineluctably spin out of the one cherished by the author and his late friend, especially in countries without a long tradition of the rule of just law.

Also, it takes particular, and in matters political particularly Russian, ignorance not to realise that “utilitarianism” isn’t a denial of the “Enlightenment values”, but as much their assertion as are “rationalism” and “progress”. Or that the central element of the worshipped triad, Equality, makes the other two impossible. Or that “the values of liberty and human rights” come from Christianity, not from the mayhem “in the very 1789 sense”.

I don’t intend to launch a frontal assault on “the camp of Liberty-Equality-Fraternity”. That would be repeating myself, as the readers of my books and surfers of this space will confirm.

The passage above is only an illustration of the paucity of thought evinced by the only available Russian opposition to Putin. With enemies like that, he doesn’t need friends.

That period during Mongol rule left an impression on the Russian of how to rule? Russia even when Christian not Enlightened?