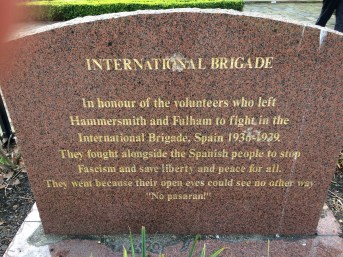

Bishop’s Park is lovely this time of year: narcissi, daffodils, magnolias, camellias and tulips are all in bloom. And then there’s this eyesore, commemorating the local residents who fought with the loyalists in the Spanish Civil War.

Bishop’s Park is lovely this time of year: narcissi, daffodils, magnolias, camellias and tulips are all in bloom. And then there’s this eyesore, commemorating the local residents who fought with the loyalists in the Spanish Civil War.

The text should more appropriately read: “To the eternal shame of those fools and knaves who fought side by side with some Spaniards to spread Stalinism and enslave first Spain and then all of Europe.”

The rousing words ¡No pasarán! the memorial extols were uttered by Stalin’s communist agent Dolores Ibárruri, during the defence of Madrid against Franco’s assault.

Ibárruri was commonly known by her nickname La Pasionaria, though it’s not commonly known how she acquired it. In fact, that crazed sadist merited the soubriquet by biting through a priest’s jugular vein, thus establishing her atheist credentials and proving herself worthy of her paymaster in the Kremlin.

The pandemic of useful idiocy clearly hasn’t been expunged, which is why even today most people assume that the wrong side won the Civil War. Franco, they say, was just awful. Fair enough, El Caudillo was no angel.

But the choice wasn’t between Franco and Mother Theresa. It was between Franco and Stalin, and still pining for the latter goes beyond simple idiocy. But of course reason has nothing to do with it. The prevailing attitude comes from the deep existential malaise of modernity.

Spain was the only European country that managed to reverse the initial success of modernity within its borders, and delay its full advent by almost half a century.

Hence Franco is still singled out for vitriol sputtered at him by every hue of modernity, in amounts far exceeding those reserved for evil ghouls like Lenin or, say, Che Guevarra.

Stalin’s Comintern mistakenly identified Spain as the West’s weakest link. The error was caused by the false Marxist methodology Stalin tended to apply to his analysis of societies he didn’t know first-hand.

The latently feudal Spain was the least ‘capitalist’ of Western European countries, which to a Marxist was a sign of weakness. In fact, Spain was at the time Europe’s most aristocratic and pious country, Christendom’s last holdout against modernity.

Not having had the benefit of a pre-Enlightenment cognitive methodology, Stalin singled Spain out for a greater dose of Popular Front subversion than any other country in Western Europe, except possibly France.

At first his strategy seemed to be succeeding. Having destabilised the transitional regime of Primo de Rivera, the Popular Front, inspired by the Comintern (which is to say NKVD’s Foreign Department), installed its own government that was eventually taken over by the ‘Spanish Lenin’ Largo Caballero.

In short order, Spain sank into anarchy, with every traditional institution being destroyed and even the army disintegrating into chaos. In Stalin’s eyes, that made the country ripe for a Bolshevik takeover: the ‘revolutionary situation’ seemed to be in place.

What Stalin didn’t realise was that Spain was perhaps the only place where Christendom wasn’t yet extinct as a social force. That the Soviet chieftain didn’t get away with this misapprehension was owed to Providence that plucked the right man out of relative obscurity and put him in the right place at the right time.

Just as the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand ignited the First World War, Franco’s revolt was triggered by the assassination of the conservative deputy Calvo Sotelo by communist paramilitaries. Franco had had enough.

He wasn’t a political general. Simple in his theoretical constructs, Franco thought along the lines of God and country and probably was uncertain where one ended and the other began.

He succeeded because his country, unlike most others, hadn’t had to endure a century of modern erosion. And Comintern subversion had had merely a decade to wreak havoc – enough time to plunge the country into anarchy, but not enough to corrupt it to the core.

There was enough spunk left in Spain, and all Franco had to do was channel it into the right conduits. This he proceeded to do, armed not only with patriotism but, fortunately for Spain, also with pragmatism.

That enabled him to look for help anywhere he could find it. Internally, it led to an alliance with the fascist Falange; externally, to one with Mussolini and Hitler. Actually, an alliance is perhaps an inadequate word to describe what essentially was a one-sided arrangement. Franco accepted Hitler’s help but managed to promise nothing but money in return.

Not only did Franco refuse to enter the Second World War on Germany’s side, but he even denied Hitler the right of passage to Gibraltar. Franco joyously traded salutes with the Nazis, but balked at trading favours. It was by design that he was so unreceptive to Hitler’s overtures that the latter likened talks with Franco to having his teeth pulled out.

Even as Paris was worth a mass to Henri IV, Madrid was worth an outstretched right arm to Franco. But he was far from being the fascist of modern mythology.

Franco was the leader of the anti-communist coalition that also included Carlist monarchists, devout Catholics, conservatives and simply decent people who understood the evil of communism.

Franco was the last defender of Christendom among the great leaders of the world, which earned him the undying enmity of the full political spectrum of modernity. For modernity detests Christendom above anything else.

That’s why the International Brigades, Stalin’s Comintern army, could boast roughly 1,000 times the number of British volunteers that Franco could attract. Stalin was a champion of modernity; Franco of Christendom.

(Peter Kemp was one of the few British volunteers who fought with Franco, in the Carlist forces. His book The Thorns of Memory is a moving account of that time.)

In the face of that difference, the relatively insignificant political disagreements among the moderns were swept aside. As his Homage to Catalonia shows, even someone like George Orwell had more in common with Stalin than with Franco. (Orwell fought with POUM anarchists, and he thought Stalin wasn’t hard enough.)

Now, almost eighty years after the Civil War, and forty since Franco died, moderns still haven’t relented. To them it’s immaterial that, but for Franco, Spain would have been turned into something like Romania c. 1950.

Modernity will never give Franco the benefit of the doubt. Even Lenin, Stalin and – in France especially – Trotsky are still seen as having possessed redeeming qualities, much as those are begrudgingly admitted to have been offset by unfortunate brutality.

Yet Franco, who saved his country from the rack of modernity, rates nothing but visceral hatred. That’s why, much as I’d like to campaign for the removal of that eyesore from my favourite park, I won’t. I’m too old for futile gestures.

Thank you for this.

My girlfriend, as you know having met her, is Spanish and I thought it necessary to devour as much Spanish history as possible – along with learning the language, as we intend to spend most of the year in that country (we currently live in Paris and speak ‘Franglais’ at home).

As a boy (circa 1976) I lived in Gibraltar for a couple of years, where my father was stationed with the Army. The border with La Linea was closed because of ‘that nasty brute Franco’ who had died the year before (although taking a boat up the coast to Estapona and Marbella was, I suppose, an early example of free movement – passports were not required). I was always struck at how open Spain was then – tourism was exploding around that time and can remember asking my father why, if Franco was such a Nazi aligned fascist, Spain was a safe haven for downed allied airmen, or escaping POWs during WW2.

Further reading has led me to the conclusion that Franco was the saviour of Spain – that is he saved it from socialist republicanism (or even Stalinism as you eloquently argue). A ‘dictator’ hands power over on a ‘like for like’ basis – either to a family member, or one who is similarly dictatorial. Franco devoted his ‘totalitarianism’ to restoring those institutions damaged by the left, over decades, allowing Spain to return to a christian monarchy and named Juan Carlos as his successor (Juan Carlos’s father, Juan, being deemed too liberal – following his father, Alphonso’s rejection of monarchy). Franco, of course, envisaged an absolute monarchy – but, nevertheless, his reforms made the transition to constitutional monarchy, which Juan Carlos opted for, seamless.

My girlfriend agrees – although she cautions that this is not a ‘fashionable view’ in large parts of Spain and one needs to be careful where and when one espouses it. The left, it would seem, are a cancer which requires endless surgery.

I once espoused that view in Barcelona, where it was at its least fashionable. After a Lucullian dinner in Barcenoleta, amply irrigated of course, we were driving back to the city centre. There were crowds of promenading Catalans all along the route, which inspired my wine-addled brain. I rolled the window down, screamed “Viva Generalissmo Franco! Viva El Caudillo!” – and hit the accelerator pedal. At that time (1990), every town in Castille had a Calvo Sotelo street or a Genral Mola avenue – but in Barcelona things were rather different. Oh to be young again.

Franco seems to have behaved as a cunning political animal and a good Catholic although he lacked the compassion which could have prevented the continuing rifts . It was a masterful move to demand so much of Hitler at the start of WWII in order to be rebuffed and escape from returning previous favours. To ask to be given the French colony of Cameroon was very close to causing the Fuhrer to bite the carpet since it was formerly the German colony of Kamerun and was no doubt earmarked to resume that role in due course. Orwell was not a political animal but as a commentator he did perceive that Stalin and Franco had the common aim of crushing any tendency of the great unwashed to take matters into their own hands. In that sense, Stalin served Franco rather well. The British government remained neutral and this enabled the maintenance of a British embassy in WWII to counter the influence of the German one.

Many of those in the International Brigade were Trotskyites and shot by Stalinist NKVD fighting in Spain.

Whatever happened to the shipment of gold as stolen by Stalin and sent to the Soviet Union during that war? Never heard how that issue resolved. Alexander has an idea?

The entire gold reserves of the Spanish Republic were shipped to the Soviet Union, partly as payment for the armaments and partly for ‘safe keeping’. The gold has never been returned. The whole operation was carried out by Alexander Orlov, NKVD head in Spain. Later he defected and lived the rest of his life in the US.