Of course it is. Unequivocally. Absolutely. Unreservedly.

All God’s children know that a free economy will outperform a command one every time, making people more prosperous and freer.

The devil’s spawn, communists, know it too. They just pretend to hate free markets for ideological reasons.

Now that’s rotten by definition. Any ideology is faith without God and thought without reason. Therefore, an ideology is always pernicious, even – and this is a key point – if we happen to agree with its central tenet.

For unequivocal, absolute and unreserved faith in free markets becomes pernicious too, if lowered down to the level of ideology. Suddenly we’re looking not at sound thought but at reductio ad absurdum.

This highlights the fundamental difference between conservatives and libertarians. And this difference doesn’t become any less fundamental just because the two groups share most of their ideas.

Both believe in individual freedom and property rights. Both are prepared to worship at the altar of free enterprise. Both want to reduce state power to the lowest sensible level.

And yet they’re as typologically different as different can be.

A conservative becomes one because of certain character traits, distrust of extremes being one, capacity for sound dispassionate thought another, tendency towards Christian love another still – this, even if he’s no churchgoer or indeed a believer.

As such, he’s not an ideologue, though at his best he may be a philosopher.

A libertarian, on the other hand, is an ideologue par excellence. He sees any moderation as apostasy, any deviation from his fiery beliefs as treason, any balanced thought as a sign of weak-kneed hesitancy.

Though he’s different from communists in everything he believes, temperamentally and, if you will, methodologically, he’s closer to them than to conservatives.

Allow me to illustrate. A week or so ago, I returned to London after three months away. Driving down my end of the King’s Road (both New and Old), I observed a scene that appalled me as a conservative, but one that would gladden the heart of a libertarian.

Until a couple of years ago, the King’s Road had been free of High Street chains, the Old end mostly, the New end entirely. At our, New, end every shop was a one-off, including a row of antique shops at the point where Old becomes New.

Then the commercial rents went up, or rather shot up. Overnight, individual shops began to go out of business one by one: they couldn’t cope with the rent hike. But national chains could.

At the Old end, one business whose rent wasn’t raised by much was the wallpaper shop Osborne and Little. As an inveterate believer in the good of human nature, I refuse to believe that their bit of good luck had anything to do with the scion of the Osborne family being Chancellor of the Exchequer at the time.

Now For Rent signs are all over the place, soon to be occupied by national chains. Many of the great antiques shops are boarded up, which is awful to see even though I could never afford to darken their threshold.

The libertarian would rejoice, or at least see nothing wrong in the development. The owners of the commercial properties exercised their rights within the framework of free enterprise. The properties are theirs, and they can set the rents at any level they wish.

The ideology was thus served. But was the good of the community?

If we define it in monetary terms only, then yes, probably. However, if we shift our vantage point, things appear to be less clear-cut. I’ll illustrate this on the example of food shopping, which is the only kind I ever do.

First, though a supermarket can offer a greater variety of food than a local butcher, fishmonger and greengrocer, the small shops generally offer better quality.

When old people complain that tomatoes have no fragrance these days and chicken no taste, they’re not just grumbling for the sake of it. And, contrary to the popular adage, nothing is worse than sliced bread peddled by supermarket chains.

Supermarkets have to buy centrally, which means that, say, fish would first be delivered to a central distributorship and only then taken all over the region. This normally takes several days, and by the time the fish reaches your frying pan it’ll have lost much of its taste, texture and nutritive value.

By contrast, a local fishmonger goes to a wholesale market at six in the morning, opens his shop at 10 and sells you fish caught within the last 24 hours.

He and his colleagues, dealing in other foods next door, thus offer a valuable service, which supermarkets can’t match. And even the price difference can be reduced in a variety of ways.

This brings us to another benefit of local shopping, one that goes beyond the freshness of the food you buy: the local shop provides a personal service.

The fishmonger knows his customers; they’re also his neighbours, occasionally friends. He is aware of what they like and what they can afford.

If some of them live in strained circumstances, he could perhaps charge them a little less, especially if they came in just before closing time. In addition, he’d be pleased to give them things like heads and bones for stock free of charge.

(Conversely, I know a fishmonger who always – objectionably!!! -overcharges customers who pull up in a Ferrari or a Lamborghini.)

Customers may still perhaps pay a little more than at a supermarket, but that could be worth it to those who’d rather be treated as individuals than as ciphers, and also to those cursed with sensitive taste buds.

Old people also used to look forward to their daily shopping outings as a chance to have a friendly chat with the owner and other neighbours who happen to be there at the same time.

In short, the local shops promoted the community spirit and a sense of togetherness – something one wouldn’t normally expect from a sprawling U-Save miles away. Add to this the better quality of their food, and we see a clear incentive to curb the natural tendency to monopoly so typical of big modern businesses.

The only way to stop this shopping landslide is for the local government to fix commercial rent rates, in ways in which residential rates are controlled in, say, New York.

A libertarian would throw his hands up in horror: this would be a gross affront to the ideology of free enterprise. A conservative just might be prepared to compromise his general principles for a particular benefit – he’s used to weighing things in the balance.

Hence the conservative answer to the question in the title is yes, usually. But he’ll refrain from obtusely insisting on yes, always.

P.S. Philip Collins, writing in today’s Times, takes exception to Lord Sacks’s equating Corbyn and Powell (see my article the other day). Powell, he says, was much worse. I’d suggest that such views are best aired in The Guardian or, better still, the Morning Star. Just to think that The Times used to be a conservative paper.

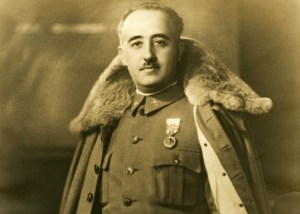

Spain’s socialist government has decreed that Francisco Franco no longer deserves to have his remains interred in the Valley of the Fallen memorial.

Spain’s socialist government has decreed that Francisco Franco no longer deserves to have his remains interred in the Valley of the Fallen memorial.